• By Christie L. Goodman, APR • IDRA Newsletter • March 2023 •

Demetrio Rodríguez, lead parent plaintiff in the original Texas school finance suit in 1969, said simply: “I wanted to have adequate schooling.”

By 1994, his dream having slipped away for his children and his grandchildren, he still held out hope: “I want my great-grandchildren to have adequate schooling.”

Rodríguez was among the Concerned Parents Association who filed suit against the Edgewood school district and five other districts in Bexar County. The parents’ concerns were sparked by students who walked out of schools across south Texas, including Edgewood students. They protested curricula that pushed them away from college and toward manual labor, and they protested crumbling facilities and inadequate funding.

The parents’ concerns also came from seeing their children’s experiences in school that fell dramatically short of their dreams for their families.

The parents went to court in 1968.

IDRA’s founder, José A. Cárdenas, Ed.D., was appointed superintendent of Edgewood ISD in 1969. He offered to testify on the family’s behalf and to support their case. He worked with them and their attorneys, advising them to redirect the case. Instead of suing other nearby poor districts, who (1) were in the same boat and (2) had no influence on the state’s school funding system, the parents shifted to take on the State of Texas.

A few months after the lawsuit was filed, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights’ six-day hearing in San Antonio on the civil rights issues of Mexican Americans. The hearings highlighted the low levels of education for students of color with averages of only 6.2 years for Latinos and 8.7 years for Black students.

The disparities in per-student funding glared. In 1970-71, Edgewood ISD could spend only $418 per pupil while Lipscomb CSD, a property-wealthy school district, spent $7,332. And Edgewood wasn’t even the lowest. That moniker went to nine other districts down to Myrtle Springs at $328 per pupil. These low-wealth districts were forced to tax at much higher rates than property-wealthy districts to even generate what little they could. (IDRA 1973)

“The Rodríguez decision is seen by many legal scholars as one of the worst Supreme Court decisions in the last century and a real betrayal to the promise of Brown v. Board of Education,” said Celina Moreno, J.D., IDRA President & CEO.

Students experienced the effects of these funding disparities every day. Demetrio Rodriguez’s son Alex recalled that the third floor of his elementary school was condemned. When it rained, water poured down the stairs. Several students had to share a single old textbook. (Barnum, 2023)

Albert Cortez, Ph.D., IDRA’s former director of policy until his retirement, recalled his days as an Edgewood ISD student in the 1960s and early 1970s: “I remember being in a typing class, and there were not enough typewriters for all the students who were taking the class. The keyboard was painted on some of the desks for those students who couldn’t work with a typewriter.”

The three-judge federal court panel issued its ruling the day before Christmas Eve in 1971 when schools and institutions were closed. Rodríguez vs. San Antonio ISD had been a sleeper case until that moment – until the ruling declared the Texas system of school finance unconstitutional, and by implication and precedence, most other state systems of school finance.

Dr. Albert Cortez explained, “The State of Texas didn’t do a very good job of defending something that frankly was indefensible.” The federal judges saw all the evidence that was presented and agreed with the plaintiffs – the families – that education and access to educational opportunity was a fundamental right under the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The court also ruled that the level of inequity that existed in the state of Texas was unconstitutional, essentially mandating the state to make major changes.

The chairman of the State Board of Education, Ben Howell, stated: “What the federal court gave us on December 23 was no Christmas present; it was a bomb. In fact, it was an atomic bomb!” (Cárdenas, 1997)

Dr. Cárdenas reported that much of the reaction was hostile: “The Texas tradition, at least among the individuals and groups with the greatest wealth and political power, is to detest interference by the federal courts in ‘the way we run our schools.’” (1997)

But in other circles, he says this period was “characterized by extensive activity, interest and optimism. It seemed that everybody wanted to know what the court decision implied.” Thus, he gave countless interviews and made frequent presentations about the school finance system, the court case and recommendations to achieve equitable funding.

He and the families made such a stir that a superintendent from a high-wealth school district “had been asked to inform me that if I could get the plaintiffs and the district to back off from the Rodríguez case, I would be guaranteed a long, successful and lucrative professional career in the high wealth districts of Texas.” He responded by asking if he could take the 24,000 children of Edgewood with him. Crickets. (1997)

But finally, the media, public officials and the general public started to see the disparities affecting students.

For years and years, IDRA led efforts to achieve school finance equity and was instrumental in the state-level Edgewood court cases, litigated by MALDEF and others, that followed the Rodríguez case.

Then came the U.S. Supreme Court’s reversal: a 5-4 ruling that, despite the observation that the Texas system was “chaotic and unjust,” it did not violate federal equal protection requirements. The ruling left it up to states to decide if all students should have well-funded public schools – a task that states did not rush to do. The ruling effectively shut down pending school finance cases in other states like California and New Jersey.

“The Rodríguez decision is seen by many legal scholars as one of the worst Supreme Court decisions in the last century and a real betrayal to the promise of Brown v. Board of Education,” said Celina Moreno, J.D., IDRA President & CEO.

Less than a month later, Dr. Cárdenas reluctantly submitted his resignation as Edgewood ISD superintendent to pursue full-time what was to become a multi-decade quest for school finance equity.

He reflected: “When I started with Texans for Education Excellence in 1973 (which soon became the Intercultural Development Research Association), many people in positions of power – the Texas governor, legislators and school superintendents – said they would be happy to change the school finance system but did not want the federal government shoving it down their throats. Naive in my heart, naive in my soul, I figured in a few years, two maybe four, that we would devise a system that everybody would support and that the problem would be solved quickly. It was not until about four or five years later that it started to dawn on us that it was not going to be as easy as we thought.” (Romero, 2001)

María “Cuca” Robledo Montecel, Ph.D., IDRA President & CEO from 1992 to 2019, stated: “When it comes to education, in America we have a society that still tolerates ‘separate and unequal.’ How else can we explain why school districts around the country with the most student poverty, have the least funding per student? In Texas and around the nation, high-poverty schools are under-resourced schools. They are most likely to have overcrowded classes, weak curricula, under-trained teachers, low test scores and high dropout rates… But the promise of quality education is America’s promise not to the privileged few but to all our children. The success in keeping our word is America’s success.”

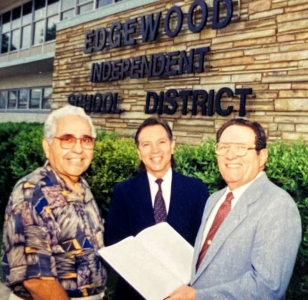

1997 Archives: Dr. José A. Cárdenas (right) presents a copy of his new book, Texas School Finance Reform: An IDRA Perspective, to Demetrio Rodríguez (left), lead litigant in the Rodríguez vs. San Antonio ISD case, with Dr. Albert Cortez (center), IDRA director of policy and school finance expert. The textbook is out of print but is available from IDRA free online: https://idra.news/TSFRbook

IDRA emerged as the only entity in the state at the time dedicated consistently to the reform of the public school finance system. IDRA conducted the necessary research to substantiate the claims made earlier by the plaintiffs in the Rodríguez case. IDRA provided state agencies and others with extensive information on the need for reform; prepared and distributed materials; and awakened educators, lawmakers, government officials and the general public to the inequities in the system of school finance and their implications for students’ educational opportunities.

For years and years, IDRA led efforts to achieve school finance equity and was instrumental in the state-level Edgewood court cases, litigated by MALDEF and others, that followed the Rodríguez case. IDRA’s research, legal strategy, expert witness testimony, legislative advocacy and community activism provided a blueprint for those interested in bringing about future reform in schools and other social institutions. Dr. Cárdenas literally wrote the textbook on Texas school finance (1997).

“What is good for the children of the most powerful in our society must be the expectation we set for all students,” said Celina Moreno. Prior to IDRA, she served as the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund’s trial and appellate co-counsel in the challenge against the inequity and inadequacy of the Texas school finance system. “While the Supreme Court hasn’t recognized education as a fundamental right, we know that it is a human right. And a series of Supreme Court decisions, from Brown v. Board of Education to Plyler v. Doe, reflect its importance” (2020).

In 1987, a Texas state court found that the state’s unequal school finance plan did in fact violate the Texas constitution. In the historic Edgewood vs. Kirby case (which came to be known as Edgewood I), the state’s supreme court required Texas to modify its school funding plan in a way that provided every school district equal return for equal tax effort, instituting a process for equalizing school funding throughout the state. But it would take more lawsuits and political shenanigans to push the state to get serious.

Dr. Cortez described one of the times he testified in a school finance trial: “I remember the state’s lawyer hammering away at me, asking how close to equity is close enough? ‘How close to equalization would you all be willing to accept’ – to, essentially, settle for. I told the lawyer: It’s either equal or it’s not. It’s either an equitable funding system or it’s not.”

He added: “It was insulting to be asked how many children you are willing to sacrifice so that you can ‘compromise’ to reach a reasonable settlement. At IDRA, we were never interested in being reasonable. As a matter of fact, we were often called unreasonable and unrealistic because we had the audacity to believe that it was possible to have an equitable school funding system for all kids. I believe that. I still believe that. I still think it’s possible.”

In the last five decades, IDRA and many with us have learned the critical importance of persistence. It has taken persistence in the courts and in the state capitol. It has taken the persistence of organizations like IDRA, MALDEF, the Equity Center and Every Texan. It has taken the persistence of school board members, superintendents and advocates.

And, most importantly, it has taken the persistence of families – mothers, fathers, grandparents – and students who insist that the state do its job to fund schools fairly and provide an excellent, college-ready education to every student. There’s nothing unreasonable about that.

Resources

Barnum, M. (February 27, 2023). The racist idea that changed American education. Chalkbeat.

Cárdenas, J.A. (1997). Texas School Finance Reform – An IDRA Perspective. IDRA.

Cárdenas, J.A. (February 2005). The Fifty Most Memorable Quotes in School Finance. IDRA Newsletter.

IDRA. (June 1973). Texas School Finance: A Basic Primer. IDRA Newsletter.

Gamboa, S. (November 23, 2019). Forgotten history: Chicano student walkouts changed Texas, but inequities remain. NBC News.

Kauffman, A.H. (2009). The Texas School Finance Litigation Saga: Great Progress, then Near Death by a Thousand Cuts. St. Mary’s Law Journal.

Poggio, M. (August 15, 2015). Recalling the walkouts of 1968 – A curriculum of low expectations was challenged. San Antonio Express-News.

Romero, A. (September 2001). Destined to Get an Equitable System of School Funding. IDRA Newsletter.

Vasquez, B. (December 2018). Three Decades of Groundbreaking Dropout Research – Reflections by Dr. Robledo Montecel. Texas Public School Attrition Study, 2017-18. IDRA.

Christie L. Goodman, APR, is IDRA’s director of communications. Comments and questions may be directed to her via email at christie.goodman@idra.org.

[©2023, IDRA. This article originally appeared in the March 2023 IDRA Newsletter by the Intercultural Development Research Association. Permission to reproduce this article is granted provided the article is reprinted in its entirety and proper credit is given to IDRA and the author.]