• IDRA Issue Brief • By Morgan Craven, J.D., & Joanna D. Sánchez, Ph.D. • April 2023 • See PDF in English • See PDF in Español •

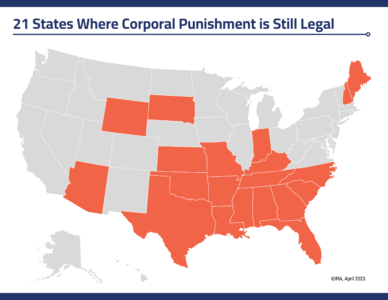

Texas is one of 21 states in the United States that allows corporal punishment in schools. Thousands of young Texans are hit in their schools every year, despite research showing that corporal punishment harms students physically, emotionally, socially, and academically and creates unsafe school climates. This practice has persisted for far too long in Texas schools, even as it is prohibited in other state-regulated settings, including foster care placements and Texas Juvenile Justice Department facilities (Texas DFPS, 2017; TJJD, 2022). The Texas Legislature has the power to stop this outdated, harmful and unnecessary form of school-based violence and must use that power immediately.

Texas is one of 21 states in the United States that allows corporal punishment in schools. Thousands of young Texans are hit in their schools every year, despite research showing that corporal punishment harms students physically, emotionally, socially, and academically and creates unsafe school climates. This practice has persisted for far too long in Texas schools, even as it is prohibited in other state-regulated settings, including foster care placements and Texas Juvenile Justice Department facilities (Texas DFPS, 2017; TJJD, 2022). The Texas Legislature has the power to stop this outdated, harmful and unnecessary form of school-based violence and must use that power immediately.

Corporal Punishment in Texas

In Texas, corporal punishment is the “deliberate infliction of physical pain by hitting, paddling, spanking, slapping or any other physical force used as a means of discipline” (TEC, Sec. 37.0011). A school district’s board of trustees must adopt a corporal punishment policy in order for the practice to be used in their schools.

In Texas, corporal punishment is the “deliberate infliction of physical pain by hitting, paddling, spanking, slapping or any other physical force used as a means of discipline” (TEC, Sec. 37.0011). A school district’s board of trustees must adopt a corporal punishment policy in order for the practice to be used in their schools.

If a parent or guardian does not want corporal punishment used against their student, they must opt out of their district’s policy – in writing – each school year. This requirement can present challenges for parents who do not know their district has a corporal punishment policy, do not understand the corporal punishment policy or their right to opt out, or do not fully understand how corporal punishment may actually impact their child. These requirements do not apply to foster parents in Texas, who are prohibited from hitting children and from consenting to school-based corporal punishment for children in their care (Texas DFPS, 2017).

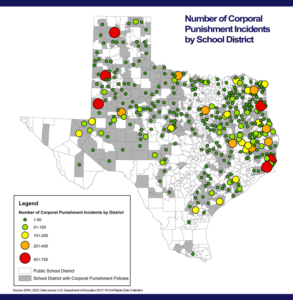

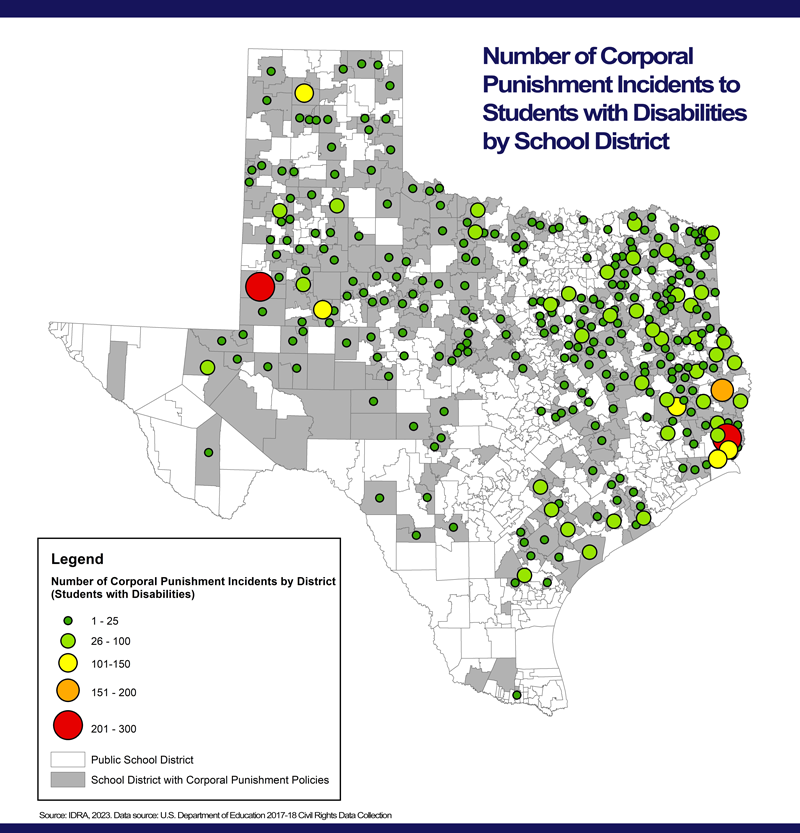

In the 2017-18 school year, 468 Texas public school districts reported having corporal punishment policies. Texas schools used corporal punishment 21,685 times to discipline 13,054 students, including preschool students (see Appendix A for a list of districts that reported using corporal punishment).

Texas reported the second highest number of students hit in the country, after Mississippi, and the seventh-highest rate of corporal punishment. These data are likely an underestimation.

Corporal Punishment in Schools is Harmful

Corporal punishment harms students and creates school cultures that prioritize hitting over evidence-based, effective strategies that create safe school environments for all students. Physically hurting students has been shown to have negative impacts on individual students and entire campus climates.

- Corporal punishment hurts students’ academic outcomes. Research shows that the use of corporal punishment in schools can limit the academic achievement and success of the students being punished and the students who see their peers punished (Dupper & Dingus, 2008; Hyman, 1996). Other analyses show negative impacts on cognitive functioning, lower performance on tests, and lower grade point averages for students who are hit in their schools (MacKenzie, et al., 2012; American Psychological Association, 2021).

- Corporal punishment hurts students physically. The stated purpose of corporal punishment is to physically hurt students and, sadly, this may be the only way the practice is effective. Students can experience significant physical harm when they are hit, spanked, slapped or paddled, including cuts, bruises and broken bones (Gershoff, et al., 2015).

As one parent shared, the paddling her young daughter received in school was so extreme she could not sit down without being in pain for days. The mother took her daughter to a doctor (though the school advised her not to) who was horrified at the brutality of the beating the child endured in school (Nollie Jenkins Family Center, 2021).

- Corporal punishment can harm students’ mental and emotional well-being. Students who are hit in front of their peers may experience trauma and low self-esteem (Greydanus, et al., 2003). They can be emotionally humiliated, feel unsafe and disempowered, and struggle with life-long depression (Gershoff, 2017). Harsh physical punishment can also lead to other mental health and substance abuse disorders (Afifi, et al., 2012; Afifi, et al., 2017).

- Corporal punishment is ineffective and even counterproductive as a discipline or teaching tool. Hitting children does not teach good behavior, and in fact may do just the opposite. Research has shown that corporal punishment is not an effective way to improve behaviors, may exacerbate behavioral challenges, and in some cases is used when students are exhibiting completely normal, age-appropriate behaviors (Gershoff, 2018). When schools rely on corporal punishment, they are not using other research-based strategies that support students and promote safer school climates.

- Corporal punishment teaches violence as a solution. Schools that model violence as a way to address conflict (real or perceived) grant permission for students to use violence, as young people and later as adults. This can compromise interpersonal relationships (Terk, 2010) and perpetuate a culture where physical violence, particularly against people of color and people with disabilities who are disproportionately hit in school, is seen as acceptable.

Who is Hit in Texas Schools

Black Texas Students are Hit More than their Peers

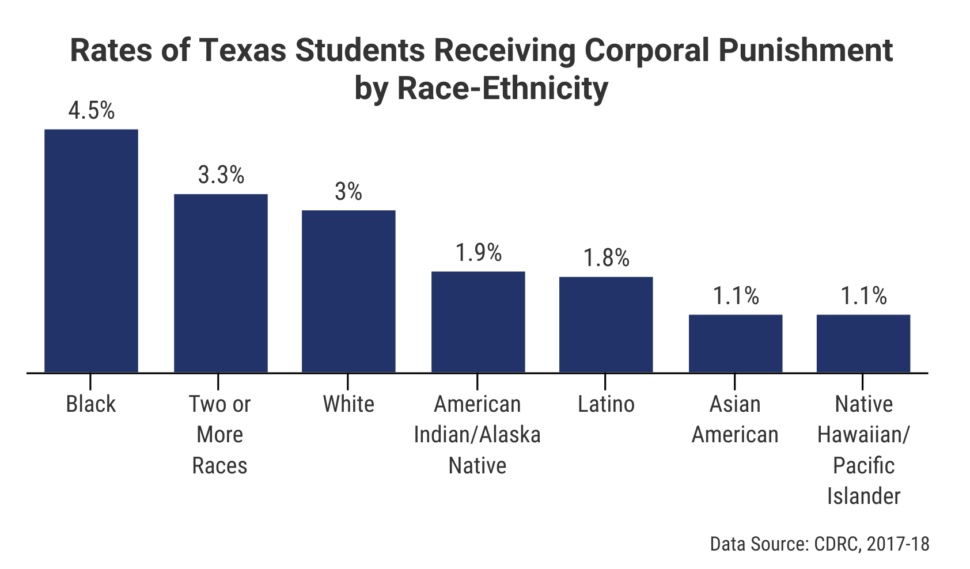

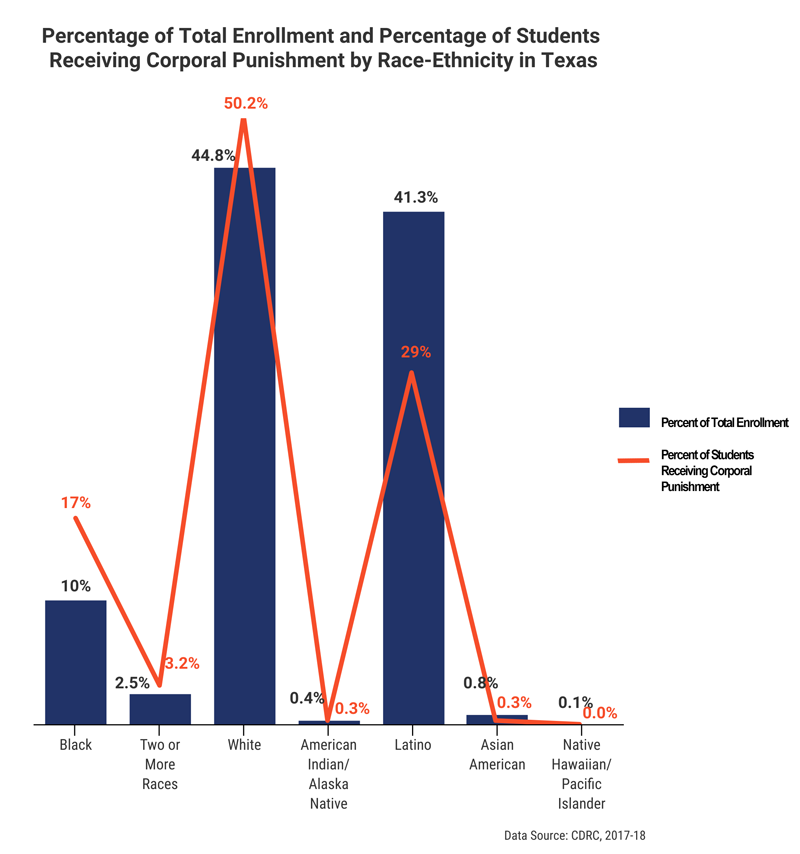

Even though Black students are not more likely to break school rules than their peers, they are more likely to be punished by their teachers and school administrators. Black students made up 10% of the student population in schools that used corporal punishment, but they accounted for 17% of children hit. Black students also experience the highest rates of corporal punishment compared to all other racial-ethnic groups. In Texas schools using corporal punishment in 2017-18, one out of every 20 Black students was hit.

Very Young Texas Children are Hit in their Preschools

Preschool students, as young as 3 and 4 years old, are hit in school. In 2017-18, Texas schools reported hitting 369 preschool students. Of all Texas students hit in their schools, 40% were in elementary school, 31% were in middle school, and 26% were in high school.

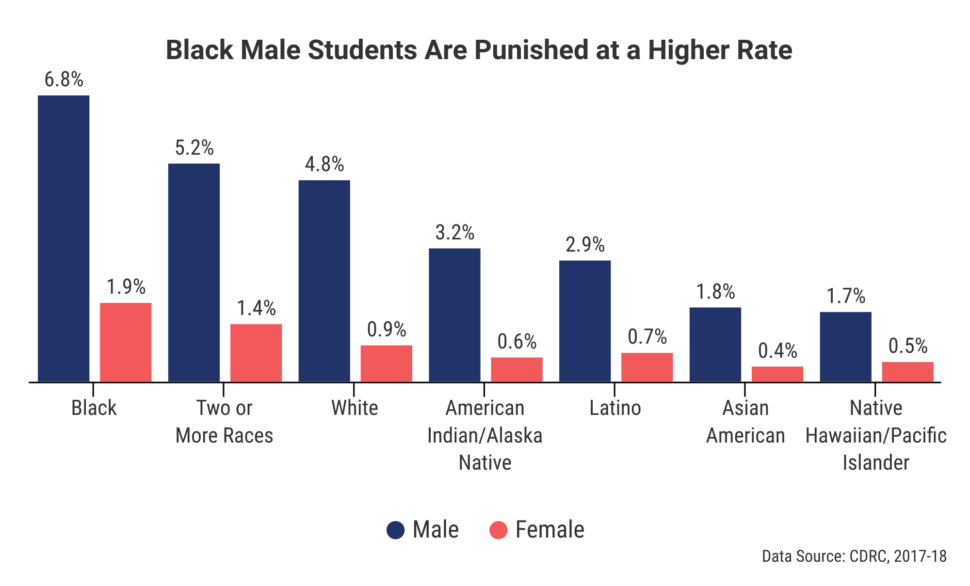

Texas Boys are Punished Most

Of the 13, 054 students who experienced corporal punishment at least once during the 2017-18 school year, male students accounted for 80% of all students subjected to this form of discipline.

Black Boys and Girls in Texas Experience Higher Rates of Punishment

Black male students are punished at a higher rate – 6.8% – than any other group. Black female students experience corporal punishment at a higher rate than female students of other races and at a higher rate than some male groups.

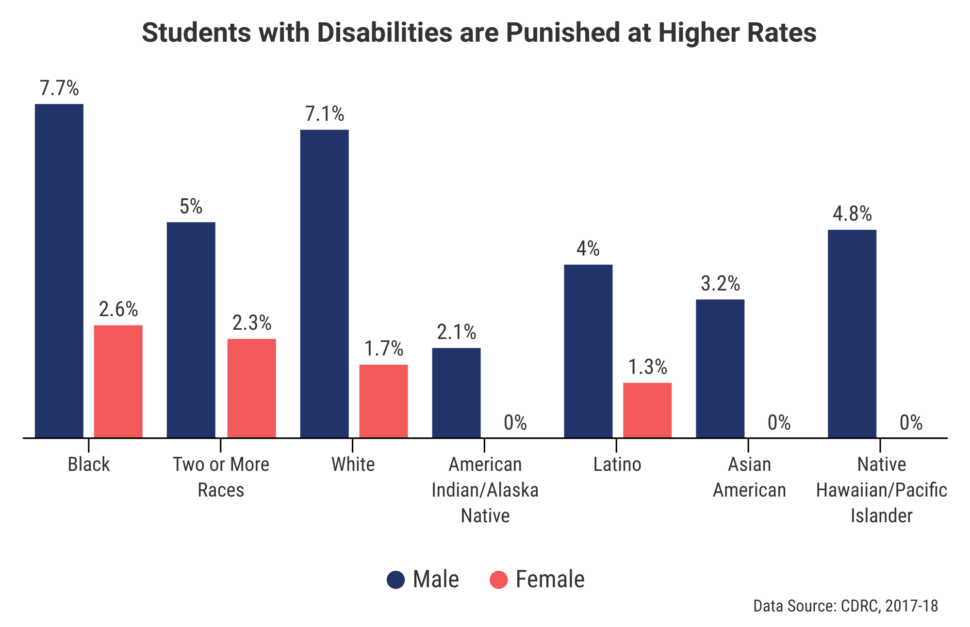

Texas Students with Disabilities are Punished at Higher Rates

Students with disabilities face higher rates of corporal punishment in Texas than their peers. Students with disabilities are punished at nearly twice the rate compared to students without a disability – 4.5% compared to 2.6%.

Those rates worsen when we consider how disability intersects with race and gender. As with other punitive discipline methods, Black boys with disabilities and Black girls with disabilities are punished at higher rates than their peers.

Ending Corporal Punishment in Schools

Texas must immediately ban corporal punishment in schools. The Texas Legislature has repeatedly failed to protect students from being hit in their schools, despite recurring legislation that has been filed to expressly prohibit the practice: It is past time to stop hitting, spanking, paddling and slapping Texas children in their schools and instead invest in evidence-based discipline and school climate strategies.

Texas must immediately ban corporal punishment in schools. The Texas Legislature has repeatedly failed to protect students from being hit in their schools, despite recurring legislation that has been filed to expressly prohibit the practice: It is past time to stop hitting, spanking, paddling and slapping Texas children in their schools and instead invest in evidence-based discipline and school climate strategies.

Districts and charter schools should end their corporal punishment policies. School district boards of trustees and charter school leaders can vote to end the use of corporal punishment in their schools and districts. These policies should be paired with policies that address other harmful punitive discipline methods, including suspensions and alternative school placements.

Schools must implement alternative practices that support student growth and promote positive school climates. All schools and districts should adopt evidence-based, culturally-sustaining educational practices, including:

- Restorative practices, positive behavioral interventions and supports, and similar evidence-based strategies used to build strong school communities, foster authentic and meaningful relationships, and repair harm between individuals should it occur;

- Ethnic studies courses, like Mexican American Studies, African American Studies, and many others that give all students a more complete and justice-centered picture of diverse groups of people in our communities; and

- District- and schoolwide cultures that focus on the strengths and assets of all students and families and employ strategies to support student and family leadership in policies and practices.

For an interactive map showing corporal punishment in Texas schools, see IDRA’s Corporal Punishment in Texas Public School Districts – IDRA Map.

For more information on adopting strategies that ensure safe schools for all students, see IDRA’s School Discipline – Online Technical Assistance Toolkit.

For more information about IDRA’s work to end corporal punishment in schools, contact IDRA’s National Director of Policy, Advocacy and Community Engagement, Morgan Craven, J.D., at morgan.craven@idra.org.

A number of national organizations have publicly opposed the use of corporal punishment against children, including (but not limited to):

- American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- American Academy of Family Physicians

- American Academy of Pediatrics

- American Bar Association

- American Civil Liberties Union

- American Medical Association

- American Psychological Association

- American Public Health Association

- American School Counselor Association

- General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church USA

- Human Rights Watch

- National Association for the Education of Young Children

- National Association of Elementary School Principals

- National Association of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners

- National Association of School Nurses

- National Association of School Psychologists

- National Association of Secondary School Principals

- National Association of State Boards of Education

- National Foster Parent Association

- National Mental Health Association

- National PTA

- Prevent Child Abuse America

- United Methodist Church

Works Cited

Afifi, et al. (2017). Spanking and adult mental health impairment: The case for the designation of spanking as an adverse childhood experience. Child Abuse Negl. 71:24-31

Afifi, T.O., Mota, N.P., Dasiewicz, P., MacMillan, H.L., Jitender, S. (2012). Physical punishment and mental disorders: results from a nationally representative US sample. Pediatrics, 130(2), 184-92.

American Psychological Association. (2021). Corporal Punishment Does Not Belong in Schools. https://votervoice.s3.amazonaws.com/groups/apaadvocacy/attachments/APA_Corporal_Punishment_Fact-Sheet.pdf citing Gershoff, E.T., Sattler, K.M.P., & Holden, G.W. (2019). School Corporal Punishment and Its Associations with Achievement and Adjustment. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 63, 1-8.

Dupper, D.R., & Dingus, A.E.M. (2008). Corporal Punishment in U.S. Public Schools: A Continuing Challenge for School Social Workers. National Association of Social Workers, 243-250.

Hyman, I. (1996). Using Research to Change Public Policy: Reflections on 20 Years of Effort to Eliminate Corporal Punishments in Schools. Pediatrics, 98(4), 818-821.

Greydanus, D.E., Pratt, H.D., Spates, C.R., Blake-Dreher, A.E., Greydanus-Gearhart, M.A., & Patel, D.R. (2003). Corporal Punishment in Schools. Journal of Adolescent Health, 32, 385-393.

Gershoff, E.T., Goodman, G.S., Miller-Perrin, C., Holden, G.W., Jackson, Y., & Kazdin, A. (2018). The Strength of the Evidence Against Physical Punishment of Children and Its Implications for Parents, Psychologists, and Policymakers. American Psychologist, 73, 626-638. doi: 10.1037/ amp0000327

Gershoff, E. (2017). School Corporal Punishment in Global Perspective: Prevalence, Outcomes, and Efforts at Intervention. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 22(51), 224-239.

Gershoff, E.T., Purtell, K.M., & Holas, I. (2015). Corporal Punishment in U.S. Public Schools: Legal Precedents, Current Practices, and Future Policy. Advances in Child and Family Policy and Practice (pp. 1-105). doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-14818-2

Nollie Jenkins Family Center (https://nolliejenkinsfamilycenter.org/). (2021). A Virtual Briefing in Support of the Protecting our Students in Schools Act. https://edtrust.zoom.us/rec/play/Gg1U9TF4G6-AjP_jh4SXT3nTqDD4-iCZkNPBGY0Mnu0aWz5oAKECDg-68urZh5sMUI6VDrNpDRuRVJt6.f3RmjpaG6LhNs8rF

MacKenzie, M.J., Nicklas, E., Waldfogel, J., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2012). Corporal Punishment and Child Behavioral and Cognitive Outcomes through 5 Years-of-age: Evidence from a Contemporary Urban Birth Cohort Study. Infant and Child Development, 21(1): 3-33.

TEC, Sec. 37.0011. Use Of Corporal Punishment. Texas Education Code. https://statutes.capitol.texas.gov/Docs/ED/htm/ED.37.htm#37.0011

Terk, J. (July 7, 2010). Corporal Punishment. Archives. https://www.texmed.org/Template.aspx?id=5662.

Texas Department of Family and Protective Services (2017). Child Protective Services Handbook. https://www.dfps.texas.gov/handbooks/CPS/Files/CPS_px_6000-2.asp

Texas Juvenile Justice Department (2022). General Administrative Policy Manual. https://www.tjjd.texas.gov/index.php/doc-library/send/495-division1-behavior-management/3171-380-9502-behavior-management-overview

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

A History of Corporal Punishment and Spanish-Speaking Students in Texas

In 1918, Texas passed laws that forbade the teaching of Spanish in schools. At the time, legislators rationalized this decision by stating that the usage of Spanish impeded upon the ability of emergent bilingual students (English learners) to learn English and “American” culture. In effect, these “no Spanish” rules banned the use of Spanish by Latino students in their classrooms and institutionalized decades of abusive and punitive practices, including corporal punishment.

This codified form of cultural and linguistic suppression was not addressed by the law until passage of the Texas Bilingual Education Act in 1969, preceded by the federal Bilingual Education Act of 1968. Despite the fact that the Act (Senate Bill 121) began the expansion of bilingual education in Texas schools, the schooling experiences of Spanish-speaking emergent bilingual students during that period remained difficult. According to Mexican American Education Study (MAES) reports, commissioned and published in the 1970s by the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Latino students who were caught speaking Spanish were exposed to physical abuse and other punishments, like fines and various forms of humiliation.

The humiliation, physical abuse, and trauma that generations of Latino Texans experienced are remembered today. Many students who endured shame and abuse in their schools for speaking Spanish then refused to teach their own children Spanish for fear that they too would be targeted in school, creating a cycle of internalized cultural suppression (Luna, 2013; Hinojosa, et al., 2021).

Following are memories of the corporal punishment endured by Latinos in Texas schools.

- “Most attending Bexar County schools at least through the 1960s in segregated schools suffered spankings and other consequences for speaking Spanish. This was a systemic stigma. Those oppressive and abusive practices marked us deeply in our communities throughout south Texas. Today that stigma remains as students try to ‘pass’ or, worse, having to deny their Mexicanismo in schools.”

- “‘Bend over’: The first English words I learned in first grade in 1959 in Sierra Blanca, Texas. I was monolingual Spanish so… spanked as soon as I began school. Very humiliating.”

- “I only spoke Spanish when I first attended an elementary school in the Edgewood ISD. Our hands were slapped with a ruler when we spoke Spanish. The most humiliating act was when I was asked to put my nose in the middle of a circle on the blackboard when I spoke Spanish. I think that is why I had a turned-up nose when I was very young, lol. Seriously, it affected us so much emotionally. My mother, who only spoke Spanish, felt helpless; she wanted us to learn English, but she did not want us to lose our native language. My grandfather felt the same and kept telling us we were worth two people by knowing two languages.”

Many thanks to Velma Ybarra and members of the Mexican American Civil Rights Institute (MACRI) for sharing their stories.

Works Cited

Gonzales, R. (September 21, 2019). Texas once banned Spanish in public schools. Fort Worth broke that mold in 1969. Fort Worth Star-Telegram.

Hinojosa, D., Robledo Montecel, M., & Montemayor, A.M. (2021). “Unmet Promises in Texas Education – Mexican Americans and Persistent Discrimination in Texas Education.” In R. Brischetto (Ed.), Mexican American Civil Rights in Texas: 1968-2018. MSU Press.

Luna, R. (dir). (2013). Stolen Education, documentary. Alemán/Luna Productions. https://www.amazon.com/Stolen-Education-EnriqueAleman/dp/B079395S6X

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. (1971-1974). Mexican American Education Study Report, series. Washington, D.C. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/102263692